Intro

The First Casualty Dissected: Introduction

The purpose of this blog, showing the extraordinary claims I'm trying to clarify, a brief description of the Operación Rosario events.

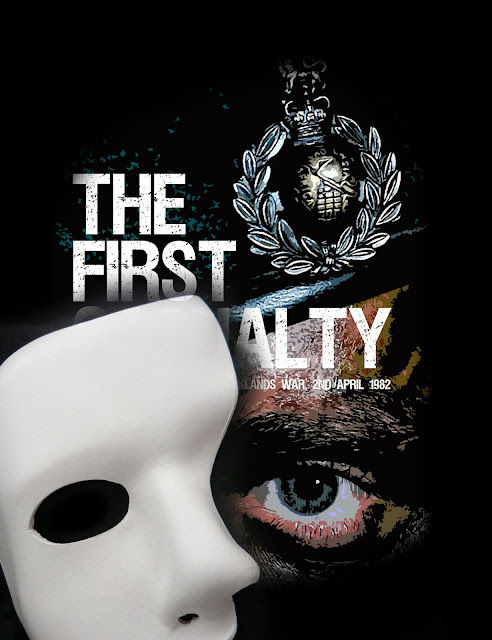

“The book they said couldn’t be written… about the battle they said never happened…”

Those

are big words rarely seen to describe history books, usually appealing

to a lower key when it comes to portray their content.

When in

2017, a book appeared to change what we knew about the Falklands War,

many people received it enthusiastically, happy to see that their

forgotten soldiers were vindicated.

Their story was indeed

relegated to a short description in the history books, and the public in

both Argentina and United Kingdom didn't get much details about how the

fighting was.

This book asserts that they not only fought

with bravery, which is by all means true, but also inflicted dozens,

maybe a hundred casualties to an overwhelming Argentine force; and that

narrative resonated with the British sentiment of many readers.

With

the first-hand accounts of Argentine and British soldiers, testimonies

from the inhabitants of Stanley, and unearthed physical evidence to proof

this assertions, The First Casualty seemed convincing; but at the same

time, very contentious.

How could a novel historian bring to light such an extraordinary information, and why was it overlooked for so long?

This blog is an attempt to show that nothing is so simple, you have to dig deeper under the surface. I think it's very important to clarify that this is not a challenge to the accounts of the Marines from NP8901, this is a challenge to The First Casualty author's methodology and conclusions.

This article summarizes the main issues found in the book:

5 Reasons why The First Casualty is wrong:

- There's no sign of battle damage on the LCVP supposedly sunk on April 2nd, 1982.

- There's pictures showing that same LCVP captured by British forces, in good condition, moored in Stanley.

- The

hole in the commander's cuppola of the Amtrac supposedly hit by the

Royal Marines, is actually the mounting point of an auxiliary viewport.

- The Amtrac's rear light cluster shown as proof of impact is a falsified piece made with a different material.

- The

damage in the Amtrac's nose section doesn't match with an impact of

HEAT ammunition. The Amtrac internal layout makes impossible to affect

the crew with an impact in that point.

In the articles listed below, you will find more detailed information:

The LCVP:

Explains the secondary role of the Landing Crafts in the Operation plans, shows pictures and video of the LCVP that proof that there's no battle damage in it; follows the procedure to identify this boat as one of the two captured in good condition by British forces after the cease fire.

LVTP-7 Intro:

A brief description of the LVTP-7 amphibious APC, their use in the Argentine Navy, their role in Operación Rosario and the combat episode in the outskirts of Stanley, showing the points where the Royal Marines claim they hit the vehicle.

LVTP-7 Cupola:

Using exclusive pictures of VAO #17, the vehicle Phillips claims was destroyed by the Royal Marines, this article demonstrates that the hole behind the cupola is the mounting point of a removed auxiliary vision periscope.

LVTP-7 Rear Light:

An analysis of the impossibility to impact the rear light from the RM positions in such a bizarre trajectory, more pictures and videos reveals that there's no sign of battle damage in the rear area; and that the rear light used as evidence by Phillips is a falsification.

LVTP-7 Nose Patch:

More pictures and videos showing that the internal damage is not compatible with Phillips theory, the impossibility to affect the crew compartment even accepting the damage was caused by a HEAT impact, and pictures of the vehicle from 1986-87 showing no damage in that area.

TFC Bibliography:

A demonstration that Phillips misquoted and mistranslated Argentine books to assert that VAO #17 was part of the Landing formation, when in fact, that vehicle was left in the barracks due to lack of spares.

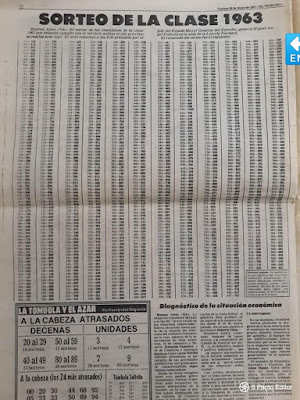

There were hidden Argentine casualties after the landing in Stanley?

The short answer is no, Royal Marines from NP8901 killed only one Argentine soldier, Cpn. Pedro Edgardo Giachino, and three more servicemen were injured: Lt. Diego García Quiroga, Cpl. Ernesto Urbina and soldier Horacio Tello, who was slightly injured in his hand. This theory is proposed exclusively by Ricky D. Phillips, a History enthusiast with no formal qualifications in History from any University. In his book, The First Casualty, self-published in 2017 and financed through a Kickstarter campaign, he affirms that up to 100 Argentine soldiers were killed in three different incidents: around 40 soldiers lost in a WWII style Higgins Landing Craft sunk at the entrance to Stanley Harbour, named locally as The Narrows; 28 troopers killed in a LVTP-7 Amphibian Personal Carrier destroyed in the eastern outskirts of the town, also known as White City; and at least 5 more casualties around Government House. These bodies were then transported to an islet north of Cape Pembroke called Tussac Island, tossed from helicopters and set ablaze with napalm to eliminate any proof of their existence.

Operación Rosario

But first, a short description of the Operación Rosario, the Argentine name for the Landing Operation. It took part in April 2nd, 1982, and consisted of two main Argentine forces: Amphibian Commandos and Tactical Divers launching in rubber boats from ARA Santísima Trinidad Type 42 destroyer, in direction of Mullet Creek, south of Stanley, with orders to attack both the Moody Brook RM barracks and the Government House; and Navy’s BIM2 Marines and a small detachment from Army's RI25 launching from ARA Cabo SanAntonio, a De Soto tank landing ship, using LVTP-7 Amphibian Personal Carriers to reach Yorke Bay, a beach north of the airport, with the objective of taking the airfield, and then proceed to Stanley to support the forces around Government House.

Armed with only small arms and a few anti-tank weapons, Norman devised a defensive tactic to delay the Argentine advance from the Airport peninsula and protect the Governor's House, the main political target of the attack.

That plan had to be reassessed when explosions and gun fire erupted around the empty barracks in Moody Brook; and Argentine Commandos were detected approaching the Governor's House from the south. The Royal Marines converged at GH to protect Sir Rex Hunt in a fierce stand against surrounding Argentine forces.